Lupus Miliaris disseminatus faciei: report of a new case and brief literature review

Main Content

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei: Report of a new case and brief literature review

Delphine Rocas MD, Jean Kanitakis MD

Dermatology Online Journal 19 (3): 4

Department of Dermatology, Edouard Herriot Hospital Group, Lyon, FranceAbstract

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei (LMDF) is a rare dermatosis with characteristic clinicopathological features but of unknown etiolgy. We report a new typical case of LMDF. A 29-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic, micropapular midfacial eruption. Histological examination revealed a dermal granulomatous reaction with central areas of necrosis and occasionally degenerated hair follicles. Workup for sarcoidosis was negative. A moderate improvement was achieved with systemic treatment with doxycycline. A brief overview of the main features of LMDF is presented.

Introduction

Lupus miliaris disseminatum faciei (LMDF), also known as acne agminata, acnitis, or Facial Idiopathic Granulomas with Regressive Evolution (FIGURE) [1] is a rare granulomatous, inflammatory disease of unknown etiology, first described by Fox et al in 1878 [2]. It is usually seen in adults between the second and the fourth decades of life [3], although it may develop also in children [4] and in elderly patients [5]. It manifests clinically with reddish-yellow or yellowish-brown papules of the central face, typically on and around the eyelids [6]. The microscopic changes include superficial granulomatous inflammation with perifollicular caseating granulomas [6]. We report herein a new typical case of LMDF and briefly review the relevant literature in order to delineate the salient clinicopathologic features of this rare dermatosis.

Case report

A 29-year-old-man sought advice for an asymptomatic eruption of the central face that had been present for some months prior to consultation. Physical examination revealed multiple (dozens) of small (1-3 mm), reddish-yellow papules present on the central face, namely the nose, cheeks, eyelids, forehead, and chin (Figures 1 and 2). The patient denied any flushing; he had no other skin lesions and was otherwise in good general condition. He was not taking any medications.

|

| Figure 5 |

|---|

| Figure 5. Improvement of the lesions 14 months after initial presentation (compare with Figure 1). |

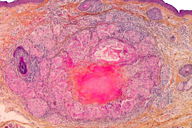

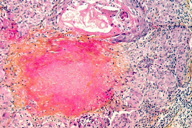

Microscopic examination of a skin biopsy taken from a representative facial papule showed a normal epidermis. The mid-dermis contained a granulomatous infiltrate forming well-defined nodules (Figure 3), centered by areas of eosinophilic necrosis of the dermis and occasionally by ruptured hair follicles. At higher magnification, the infiltrate was seen to consist mainly of epithelioid and multinuleated cells (Figure 4). Histochemical stains (PAS, Ziehl) showed no microorganisms within the granulomas. Chest X-ray and routine laboratory workup, including levels of the angiotensin-converting enzyme, were within normal limits. On the basis of these findings the diagnosis of LMDF was made. The patient was given treatment with doxycycline (100 mg/d) for several months. Moderate improvement of the lesions was achieved (Figure 5). The patient was lost to further follow-up.

Discussion

LMDF is a rare dermatosis; about 200 cases have been reported to date [6, 7]. It presents with yellowish-red asymptomatic papules involving mainly the central face. Extrafacial zones can be rarely affected, including the axillae, neck, scalp, legs, trunk and genitalia [8, 9, 11]. Patients with exclusively extrafacial lesions (neck and chest) have been reported [10]. The lesions usually regress spontanously within 12 to 24 months leaving depressed scars [11].

Histopathologically, LMDF is characterized by a dermal granulomatous infiltrate. The changes vary according to the age of lesions (early, fully-developed, and late stage). Early-stage lesions comprise a perivascular and periadnexal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. In the fully-developed stage, the following spectrum of changes can be seen: epithelioid cell granuloma with central necrosis; epithelioid cell granuloma without central necrosis (sarcoidal-type granuloma); epithelioid cell granuloma with abscess; and nongranulomatous, nonspecific inflammatory infiltration. Late lesions show extensive perifollicular fibrosis with nonspecific cell infiltration [11, 12, 13].

The etiopathogenesis of LMDF is currently unknown [11]. Originally, LMDF was thought to be a “tuberculid,” i.e., a condition related to tuberculosis [14] because of its histopathologic features resembling this infection (epithelioid cell granuloma with central necrosis). However, bacteriological cultures from LMDF lesions failed to reveal bacilli [11, 15] and studies using the more sensitive polymerase chain reaction failed to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA [16]. Therefore, the tuberculous origin of LMDF is no more accepted. Based on the fact that the granulomatous reaction frequently develops in the vicinity of a ruptured hair follicle, it has been hypothesized that LMDF is an expression of an immune response to the pilosebaceous units. According to this hypothesis, damage to the hair-follicle epithelium (occurring in the early stage) releases follicular antigens that trigger an autoimmune reaction directed against hair-follicles [12]. However, the granulomatous infiltrates are associated with pilosebaceous units in merely 43 percent of cases [3]. Other authors consider LMDF to be a variant of granulomatous rosacea on the basis of the localization of the lesions in the midface and the pathological changes, which may be similar to those seen in granulomatous rosacea. However, several clinicopathological differences exist between rosacea and LMDF. The former runs a more chronic course than LMDF. Extrafacial involement may occur in LMDF. Patients do not report flushing and the disease is not worsened by alcohol or spicy food intake. Contrary to rosacea, LMDF lesions do not contain Demodex mites [3] and they are more resistant to treatment and heal with scarring [17]. FACE syndrome (Facial Afro-Caribbean Childhood Eruption), a perioral granulomatous dermatitis resembling perioral dermatitis, is another condition of unknown etiology that should be differentiated from LMDF [18]. It affects mostly black Afro-Carribean children. The histopathologic hallmark is a dermal granulomatous infiltrate without necrosis. The lesions heal without scarring. Sarcoidosis can be clinically similar to LMDF. However, sarcoidosis may be associated with systemic manifestations (namely respiratory) and increased levels of the angiotensin-converting enzyme, features that are absent in LMDF. Pathologically, granulomatous sarcoidal lesions contain rare, if at all, central necrosis.

The course of LMDF is protracted over several months or years. The lesions regress spontanously within several months (typically 12-24), often with unsightly scarring. The treatment is unsatisfactory. The response to tetracyclines and retinoids (isotretinoin) is variable [11, 19]. A patient responding to an association of tetracyclines with isoniazide was recently reported [20]. Variable responses have been obtained with systemic treatment with dapsone [21] (alone or in association with topical tacrolimus [11]), corticosteroids, alone [22] or in association with dapsone [11], and clofazimine [23]. It has been recommended to treat the lesions early in order to prevent the development of depressed scars.

References

1. Skowron F, Causeret AS, Pabion C, Viallard AM, Balme B, Thomas L. FIGURE: facial idiopathic granulomas with regressive evolution. Is ‘lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei’ still an acceptable diagnosis in the third millennium? Dermatology. 2000;201:287-289. [PubMed]2. Fox T. Disseminated follicular lupus (similating acne). Lancet. 1878;112:75-76.

3. Shitara A. Clinicopathological and immunological studies of lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei. J Dermatol. 1982;9:383-95. [PubMed]

4. Iwasaki Y, Hata M, Sakakibara T et al. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;18:29-33.

5. Dekio S, Kidoi J, Imaoka C. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei – report of a case of an elderly woman. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1991;16:295-296.

6. Borhan R, Vignon-Pennamen MD, Morel P. [Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei: 6 cases]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2005;132:526-530.

7. Esteves T, Faria A, Alves R, Marot J, Viana I Vale E. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16(5):10. [PubMed]

8. Hillen U, Schroter S, Denisjuk N. Axillary acne agminata (lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei with axillary involvement). J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2006;10:858-860. [PubMed]

9. Van de Scheur MR, Van der Waal RI, Starink TM. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei: a distinctive rosacea-like syndrome and not a granulomatous form of rosacea. Dermatology. 2003;206:120-123. [PubMed]

10. Kim DS, Lee KY, Shin JU, Roh MR, Lee MG. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei without facial involvement. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:504-505. [PubMed]

11. Al-Mutairi N. Nosology and therapeutic options for lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei. J Dermatol. 2011;38:864-873. [PubMed]

12. El Darouti M, Zaher H. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei – pathologic study of early, fully developed, and late lesions. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:508-511. [PubMed]

13. Sehgal VN, Srivastava G, Aggarwal AK, Reddy V, Sharma S. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei. Part I: significance of histopathologic undertones in diagnosis. Skinmed. 2005;4:151-156. [PubMed]

14. Laymon CW, Michelson HE. Micropapular tuberculid. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1940;42:625-628.

15. Calnan C. Acne agminata, lupus miliaris faciei and acnitis. G Ital Dermatol Minerva Dermatol. 1966;107:587-595. [PubMed]

16. Hodak E, Trattner A, Feuerman H et al. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei – the DNA of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is not detectable in active lesions by polymerase chain reaction. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:614-619. [PubMed]

17. Khokhar O, Khachemoune A. A case of granulomatous rosacea: sorting granulomatous rosacea from other granulomatous diseases that affect the face. Dermatol Online J. 2004; 10 (1):6. [PubMed]

18. Cribier B, Lieber-Mbomeyo A, Lipsker D. [Clinical and histological study of a case of facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption (FACE)]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2008;135: 663-667. [PubMed]

19. Daneshpazhooh M, Ehsani A, Toosi S, Robati RM. Isotretinoin in acne agminata. Saudi Med J. 2007;28:1600-1602. [PubMed]

20. Ganzetti G, Giuliodori K, Campanati A, Simonetti O, Goteri G, Offidani AM. Doxycycline-isoniazid: a new therapeutic association for recalcitrant acne agminata. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:207-209. [PubMed]

21. Kumano K, Tani M, Mwata Y. Dapsone in the treatment of miliary lupus of the face. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:57-62. [PubMed]

22. Uesugi Y, Aiba S, Usuba M, Tagami H. Oral prednisolone in the treatment of acne agminata. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:1098-1100. [PubMed]

23. Seukeran DC, Stables GI, Cunliffe WJ, Sheehan-Dare RA. The treatment of acne agminata with clofazimine. Br J Dermatol 1999; 141: 596-7. [PubMed]

© 2013 Dermatology Online Journal