Nodular pretibial myxedema

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D32x2845r1Main Content

Nodular pretibial myxedema

Christopher M Hunzeker MD, Hideko Kamino MD, Ruth F Walters MD, Olympia I Kovich MD

Dermatology Online Journal 14 (10): 8

Department of Dermatology, New York UniversityAbstract

A 30-year-old man with previously diagnosed and treated Graves disease presented for consultation regarding asymptomatic nodules over his anterior tibias. He was euthyroid at the time of presentation. The nodules arose symmetrically beneath the sites of pressure from his military boots. A biopsy specimen showed an accumulation of acid mucopolysaccharides consistent with pretibial myxedema. The patient had recently stopped smoking and chewing tobacco, which are known risk factors for the development of pretibial myxedema. Following diagnostic punch biopsies, the patient experienced a rapid resolution of the nodule on his right leg and a appreciable reduction in size of the nodule on the left leg. Three months later, the nodules are beginning to enlarge once again.

|  |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|

History

A 30-year-old man presented to the Veterans Administration New York Harbor System for consultation regarding asymptomatic nodules on his shins. The nodule on his left shin had enlarged slowly and hardened over the 18 months preceding his initial visit. The nodule on his right shin had appeared and rapidly enlarged over the few weeks prior to presentation. The patient denied specific trauma to the affected areas. However, he noted that the nodules were located beneath the tops of his lace-up military boots that pressed against his shins.

The patient was serving in Iraq before he received medical leave after experiencing fever, sweating, and palpitations. After evaluation, a diagnosis of Graves disease was made in the fall of 2005. He never experienced ophthalmopathy related to his thyroid disease, and he is otherwise healthy. He was treated with radioactive iodine approximately one year ago, and, since then, he has taken levothyroxine 100 mcg daily. His only other medication is a nicotine transdermal patch 7mg/24 hours that he is using to try to quit a two-year habit of chewing tobacco and smoking one to three cigarettes per day.

Physical Examination

Nodules were present overlying the mid-anterior tibias. The lesion on the right was a non-tender, skin-colored, rubbery, firm, round nodule that measured 2.0 cm in diameter with no overlying epidermal changes. The lesion on the left was also non-tender and skin-colored and measured 2.5 cm by 2.5 cm. This lesion, however, was firmer, less well-demarcated, and demonstrated dilated follicular infundibula.

Lab

At the time of presentation, the T4 and TSH were normal. A complete blood count was normal.

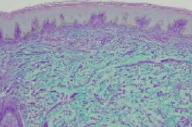

Histopathology

In the papillary and reticular dermis, the collagen bundles are widely separated by abundant deposits of mucin, highlighted by an alcian blue periodic acid-Schiff stain.

Comment

Pretibial myxedema, which also is known as localized myxedema and thyroid dermopathy, refers to the localized accumulation of acid mucopolysaccharides (glycosaminoglycans) in the dermis that causes thickening of the skin [1]. Pretibial myxedema is the most common cutaneous finding associated with hyperthyroidism and joins exophthalmos and thyroid acropachy to comprise the classic clinical triad of extrathyroidal manifestations of Graves disease.

Graves disease is an autoimmune disease of the thyroid gland that results from the production of IgG autoantibodies that are directed against the thyrotropin (TSH) receptor [2]. Graves disease is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism and affects up to 50 per 100,000 people per year [3]. Ophthalmopathy is the most common clinical manifestation of Graves disease and is present in 30 to 45 percent of patients. Pretibial myxedema and thyroid acropachy are observed less frequently and are thought to indicate more severe disease [4]. Pretibial myxedema is seen in 1 to 4 percent of all patients with Graves disease; however, the incidence approaches 15 percent in patients with severe Graves-related ophthalmopathy. Thyroid acropachy is the least common finding of the triad and is observed in only 25 percent of those patients with pretibial myxedema. Tobacco use has been shown to be a strong risk factor for the development of Graves ophthalmopathy, pretibial myxedema, and thyroid acropachy [4, 5].

Pretibial myxedema is so named because nearly 100 percent of cases of localized myxedema associated with Graves disease involve the pretibial area [5]. Lesions less commonly appear on the feet and toes, and isolated cases have been reported that involve the upper extremities, shoulders, back, pinnae, and nose [4]. Lesions most commonly present as diffuse, non-pitting edema. Additional presentions include indurated plaques with a peau d'orange appearance and, less commonly, nodules or polypoid lesions. Rarely, an elephantiasis-like presentation is observed, which has functional morbidity, as opposed to the other presentations, which are more of a cosmetic concern.

The precise pathogenesis of pretibial myxedema is not known; however, immunologic and cellular mechanisms have been proposed. An immunologic stimulation theory is based upon evidence that thyrotropin receptor antibody binding sites have been demonstrated in pretibial fibroblasts [4, 6, 7]. Stimulation of these fibroblasts produces large amounts of hyaluronic acid. A second theory hypothesizes that T cells sensitized to antigen or antigens that are shared by thyroid follicular cells and fibroblasts (eg. a portion of the TSH receptor) infiltrate dermal tissue, release cytokines, and stimulate the synthesis of acid mucopolysaccharides [3].

Neither theory explains why myxedema appears, in most cases, exclusively in the pretibial area. One hypothesis is that trauma is a predisposing factor. Evidence to support trauma as a contributing factor includes cases of myxedema localizing in skin grafts, surgical scars, immunization sites, and areas of repetitive trauma [4, 8, 9]. It is plausible that trauma to cells in the pretibial dermis begins a cascade of inflammatory cell influx, cytokine release, and fibroblast stimulation.

Our patient's presentation was very typical in many regards; he was euthyroid after the treatment of Graves disease. He had asymptomatic lesions that are symmetrically located in the pretibial area where his military boots pressed upon his tibias. He both chewed and smoked tobacco. The unique aspects of this case include the asymmetry of the lesions with regard to firmness and duration. The nodule on the right arose rapidly over the course of a few weeks, whereas the left nodule had been present for eighteen months. Our patient's lesions responded to diagnostic punch biopsies. Two weeks after the biopsies, when the patient returned for suture removal, the new lesion on the right had resolved completely and the longer-standing lesion on the left had decreased in size by nearly 50 percent. In a recent phone coversation with the patient, he said that nodules are beginning to reappear, nearly three months after the biopsies were performed.

Treatment of the underlying thyroid disease may not improve pretibial myxedema; however, it is the most important aspect in management. The patient should be referred to an endocrinologist for evaluation and treatment if this has not been done. Observation is reasonable for asymptomatic and mild pretibial myxedema. Moderate disease can be managed with topical or intralesional glucocorticoids. Because it is rarely necessary, the evidence for effective aggressive therapies for advanced disease is lacking. Oral glucocorticoids, plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulin, octreotide, and surgical therapy have been tried with varied success [4, 5]. A majority of patients experience partial or complete remission of lesions over time, and resolution of lesions is more heavily dependent upon the severity of the disease than on the treatment regimen employed.

References

1. Georgala S, et al. Pretibial myxedema as the initial manifestation of Graves' disease. J Eur 2002; 16: 380 PubMed2. Anderson CK, Miller OF. Triad of exopthalmos, pretibial myxedema, and acropachy in a patient with Graves' disease. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003; 48: 970 PubMed

3. Mclver B, et al. The pathogenesis of Graves' disease. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1998; 27: 73 PubMed

4. Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol 2005; 6: 295 PubMed

5. Schwartz KM, et al. Extensive personal experience - dermopathy of Graves' disease (pretibial myxedema): long-term outcome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87: 438 PubMed

6. Cheung HS, et al. Stimulation of fibroblast biosynthetic activity by serum of patients with pretibial myxedema. J Invest Dermatol 1978; 71: 12 PubMed

7. Stadlmayr W, et al. TSH receptor transcripts and TSH receptor-like immunoreactivity in oribital and pretibial fibroblasts of patients with Graves' ophthalmopathy and pretibial myxedema. Thyroid 1997; 7: 3 PubMed

8. Schwartz KM, et al. Development of localized myxedema in a skin graft. Int J Dermatol 2002; 41: 401 PubMed

9. Missner SC, et al. Graves' disease presenting as localized myxedema in a thigh donor graft site. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998; 39: 846 PubMed

© 2008 Dermatology Online Journal